Thursday, 15 August 2013

NOW TV box: a mini-review

Firstly, given the price, there's obviously a catch, which in this case is "Sky by stealth". We've never had any sort of Sky product, so now they have our contact details plus viewing habits via the box, which is presumably worth the cost of subsidising the box alone. It's also very firmly squared at tempting viewers into premium Sky packages (sport and movies).

But the fact there was a catch was obvious, and it doesn't detract from the product itself. So how does it hold up?

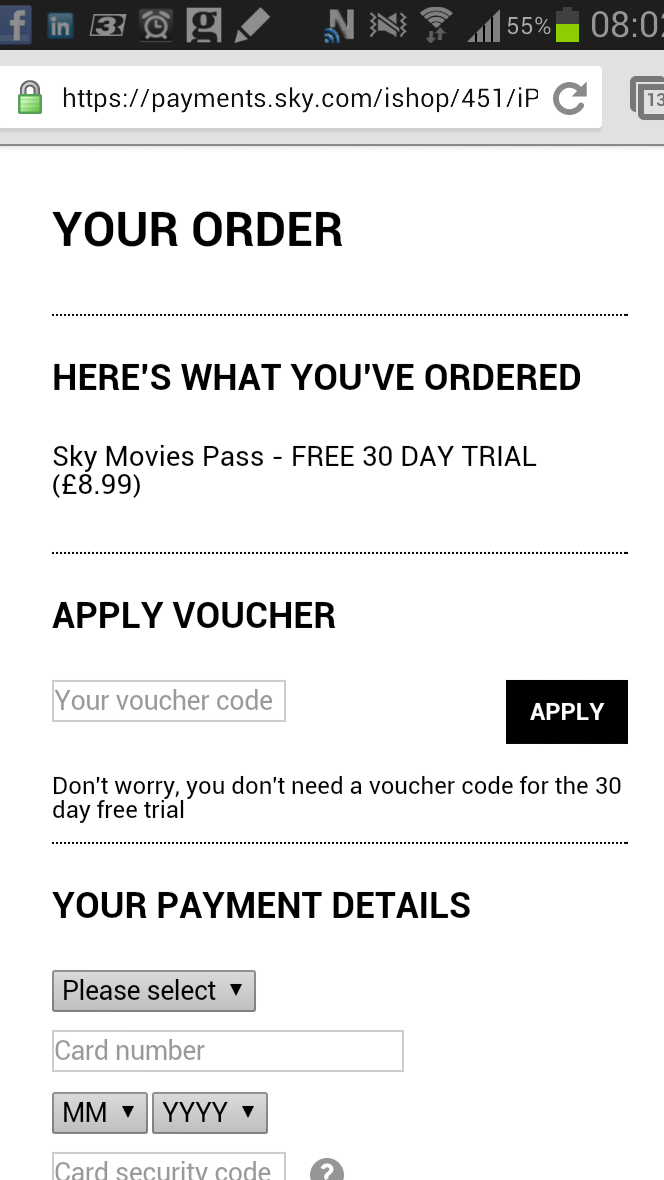

The box itself is small, unobtrusive and simple to set up. Getting started out-of-the-box iss a matter of minutes. Yes, you'll need to have wifi and a HDMI port in your TV, but most people will have those these days. The only slightly finicky thing about setup is that you need to have a "NOW TV account" which is different from the details you give Sky when ordering the box itself. I may be wrong, but it seems to create an account you either need to order a Sky Sports Day Pass (£10) or sign up for a month's free trial of Sky Movies. I opted for the latter and got as far as this screen:

Shurely shome mishtake? Impressively quick customer service from @NOWTV replied to my cynical tweet and assured me that the trial would indeed be free, but even so I see no reason to provide my credit card details for a free service (isn't that what porn websites do?). Hint: if you get as far as this screen, you'll already have a username and password on the site, so you can abort your oder at this point and still have enough details to get the box started.

Functionality itself is pretty limited but has one major strength, namely the ability to get iPlayer onto a non-smart TV. This in itself is the main benefit and makes it worth the price. There's also Channel 5 on demand; apparently ITV and Channel 4 are in the pipeline, which would be nice.

There are other apps - most of which are pretty pointless, although being able to watch TED talks on TV is quite cool. In addition, for non-smart TV owners like me, there's no obvious way to download films to a TV, so the fact that Sky have sneaked in there with a cheap box means that if I want to download a film, I may just go with Sky's NOW TV service, purely for convenience.

Vimeo is included but YouTube is not, which is a major drawback. I'll also have to wait for Google to release their Chromecast before I'll be able to watch BT Sport on the TV rather than the laptop, which is irritating. So for the moment I'm thinking of it as an iPlayer-only device.

However, the ability to buy a Sky Sports day pass is a major attraction for me. Priced at a tenner, it's teasingly affordable compared to the £40-odd I'd need to shell out for a full-blown subscription. Previously, the day passes were only available via my PC, so I may well pay for the occasional day watching the Ashes, Ryder Cup, Heineken Cup or similar. So Sky are likely to take some of my money which they otherwise wouldn't have had. It's clever marketing, in a way that both Sky and the customer are winners in their own way.

Overall: don't be fooled into thinking this is some sort of all-singing all-dancing device; it's just a way to get iPlayer onto your TV if you can't do it already. But for that alone, the giveaway price is worth it, and having the technology in place to allow you to get bite-sized versions of Sky premium products (ie sports and movies), combined with the simplicity of the product itself, make it a thumbs up from me.

Monday, 16 April 2012

Sarashwathy Bavans, Wembley - review

If you're the sort of person who's bothered by the decor of a restaurant then you're unlikely to be the sort of person considering a trek up to Wembley for a meal, but suffice to say it's basically a white-walled, strip-lit diner. Not first date material unless your date is in the top percentile of interestingness and/or open-mindedness.

On the Saturday evening we were there, several Asian families were dining, some with young kids; to our left seemed to be a large family party with about fifteen people, mostly guzzling dosas, which the restaurant professes to specialise in. We've ordered dosas the last few times we've been in South Indian places (although a mate and I ordered a couple of lovely spinach dishes recently for a home delivery from Kovalam on Willesden Lane) so this time decided to go for different options.

To start we went for idly (a light ground rice/lentil cake) and methu vadai (lentil doughnuts) which came with a selection of chutneys. The methu vadai, in particular, were delicious: a strong nutty flavour - possibly a mixture of cumin and mustard, but I couldn't be sure.

|

| The wreckage of an idly with various chutnies in the background. Far left: salt lassi |

Crucially, though, the waiter (who perhaps detected a little hesitation when we came to ordering) confidently asked "May I make a suggestion?" EXACTLY what I like to hear. He suggested reducing the quantity of idly and adding some "mushrooms 65". We had no idea what these were but were happy to place ourselves in the hands of the expert - wisely so: the mushrooms were excellent. Fried in a mixture of spices, they were very dry and packed some proper heat - mango chutney provided relief. Apologies for the appalling photography.

|

| Mushrooms "65" hidden somewhere underneath the onion rings! |

|

| Mutter paneer: fantastic food, not-so-fantastic photography |

|

| Aloo jeera - potatoes in cumin seed |

|

| Something hot, sweet and delectable...and Rachel. |

Saturday, 5 February 2011

Blogger Android app - a little review

As if by magic, just a few days after I started using my new phone and implored Google to introduce an official Android app for Blogger, they've done it. The app is free and available on the Market now. But is it any good?

The app loads quickly and has a very simple interface, which is a promising start. Multiple accounts are supported, which is nice, and if you ave several blogs on the same account then these can all be updated. This reveals the first flaw: the default blog is not necessarily the last one posted to, or the most frequently updated. Mine defaults to an old, forgotten blog, which is a shame.

Understandably, formatting options are minimal, but most people wouldn't want to get that fiddle anyhow. Even on my enormous HTC Desire HD, I'll be quite happy with plain text, with the ability to update the post and make it look fancy later.

Photos can be uploaded either from the gallery, or directly from the smartphone camera; this means liveblogging from an event or news situation is easy. It certainly means that photographing directly to Twitpic is no longer the sole option.

Labels (tags) are also enabled, and there's a nice GPS feature, so that the blogger's action can be automatically added: a nice.touch.

All of this is very nice, but the official app doesn't really do anything that Blogger-droid couldn't handle. What is really criminal is that there's so syncing with the Blower account. It seems that a post from a mobile will only appear in the main account once it has been published. This means that it's not.possible to write part of a post on the go and finish it offer home on a computer, or vice versa. As someone who tends to write fairly lengthy pieces over a period of time, this is extremely frustrating - t would be nice to have a piece of work in progress bubbling away, and add to it whenever. Have an idle five minutes. The sooner Blogger sort this out the better. Some sort of spellcheck woulda be welcome, although my HTC has this built in.

All in all, the Blogger Android app does the job well enough, although I will lol forward to improved versions providing further functionality. Incidentally, I wrote this post on my phone!

Monday, 31 January 2011

HTC Desire HD - full review

Friday, 29 October 2010

Blasted (Lyric) - review

Why would anyone want to kill you?

Revenge. Things I've done.I read a lot of "pre-match hype" about Sarah Kane's Blasted, and found it difficult to shake off the stereotypes of it being a "cry for help" shortly before her suicide, and didn't know what to make of the hypocrisy (there is no other word for it) of critics, who denounced it as "filth" (among other things) at the time of its first production, but lined up to laud its genius after her death. Sean Holmes takes it on at the Lyric.

I went in braced for an onslaught of harrowing visual imagery. Blasted isn't as simple as that, however. It's a series of rather disjointed tableaux, darkly comical at times, post-apocalyptic at others, with shades of everything from Greek tragedy to Wilfred Owen to Kafka along the way.

Ian and Cate are spending idle time in a hotel. The hotel is plush but bland: perhaps a Hilton or Marriott. The nature of their relationship is never fully revealed; it is mainly sexual, abusive, domineerin on the part of Ian...but Cate does not walk away. Ian's foulmouthed misogyny and vices clearly have some sort of appeal. The dialogue is framented. Many questions are unanswered at this stage: why does Ian carry a gun?

The tone darkens as scene two opens: Lydia spits "Cunt" and it is clear that she has been violated in the night. Even now, the conversations are broken and ambiguous, Ian's paranoia ever more apparent. A soldier bursts into the room, and enages in philosophical debate about the nature of wartime atrocities with Ian. From then on, the surrealism, graphic brutality and black humour crescendo to a grotesque endpiece.

Danny Webb and Lydia Wilson take on the lead roles with mixed success. They are fearsomely difficult parts to play, and the uncomfortable chemistry that is inevitable between a foul-mouthed, abusive, paranoid alcoholic and an attractive introvert thirty years his junior, is clear to see. Webb, despite a rather bizarre accent, was excellent for the most part, although he took a while to warm up. His central conversation with the soldier (it reminded me of Owen's Strange Meeting) crackles with tension, coinciding with some of the best dialogue in the play, while his descent into the tattered rags of a man towards the end reminded me somewhat of the central character of Paul Theroux's deeply disturbing The Mosquito Coast - paranoid, self-destructing, hideous. Wilson, meanwhile, plays her part bravely, but rather surprisingly is let down by technical basics rather than a lack of depth: her hammy stutter, unconvincing movement, and inability to deliver the humorous lines, are all surely details that could be ironed out, as she tackles the uncomfortable role fearlessly.

In truth the script left me rather cold. The soldier dialogue, Ian's complete mental collapse in the later stages, and some of the black gags are terrific, but ultimately I didn't find the play particularly thought-provoking as a whole. Is it shocking? Yes, the material is pretty graphic, but again, I found it all leaving little emotion on me. Much of the attention is understandably on Ian's grapples with the morals of suicide, but these are only really interesting in the context of the playwright's situation - little original thinking is presented. Meanwhile, for truly horrifying rape scenes, look no further than The Paper Birds' In a thousand pieces or Biuro Podrozy's Carmen funebre which are both infinitely more harrowing, without an explicit scene in sight. (The Paper Birds take their latest show Others to the Camden People's Theatre in a couple of weeks). But the shocking truth for me was that it all left me feeling a bit nonplussed.

Sean Holmes left me feeling pretty flat with his Three Sisters earlier this year. This time, his production is terrific, with only irritating details from the actors letting the side down. The post-holocaust latter scenes are quite brilliant, and the final scene rightly had the audience gripped in horror. A special mention to Paule Constable's lighting, which was particularly good.

Finally, a gripe. I was running late, and charged from the tube station, thrust my tenner at the box office staff, and hurried upstairs, sweating, into the auditorium at a minute to seven. It was practically empty. I had to check my ticket to confirm that it was indeed a 7pm start. Only ten minutes later did the press night audience start wandering in, seemingly under no pressure from staff to hurry up and get to their seats, and some even wandered out again to refill their drinks. The show finally got under way at a quarter past, seemingly because the becocktaildressed PR team couldn't be bothered to chivvy the critics inside. Now, I know it's press night and there are whims to be pandered to, but that strikes me as discourteous and disrespectful to the paying punters. If there's an advertised time, there should be no reason (technical hitches apart) not to stick to it.

Verdict: a brutal but disjointed script is overhyped, but neither that nor stilted acting can spoil a thoughtful production of this post-holocaust vision. Worth seeing.

Until 20 November. Tickets from £10.

Thursday, 2 September 2010

Mark Earls - "Herd": the Da Vinci Code of marketing?

It's a beautifully printed volume - nice paper, nice typeface and a bright pink cover of the sort that makes people on the tube squint to see what you're reading (and when they see the "how to change mass behaviour" title combined with a suitably megalomaniac look in your eyes, you'll get a bit of extra standing room, I promise you). The writing style is very much in the catchy mould of the advertising professional, albeit the author is a planner by trade, not a creative. Short, sharp sentences. With lots of sentences starting with 'with'. And many more starting with 'and'.

[Update, 7 September: I'm now reading Banks' Towing Icebergs which is very interesting if you like maths, and is bringing back rather more vivid memories of differential equations than I'd like to remember; and how could I forget to link to this post comparing traffic modelling to online communities?]

Meanwhile, Mark Earls is able to cover huge amounts of ground in subjects close to his heart. He launches into a discourse on one of hs favourite subjects with gusto in the early pages. a self-confessed amateur primatologist, he explores the human/chimp boundary and concludes that socially, as well as physiologically, we are infinitesimally close: humans are an example of a super-social ape. Chapter 1 doesn't say anything particularly radical. Rather, it sets the scene for Earls' later dramas, a scene with all humans as a naturally social species, with interactions with other people playing a central role in the way we approach all problems and decisions.

The second chapter carries on where the first left off, with helter-skelter, high octane voyages of discovery covering illusions and memory - and where the two meet in the middle. Then, out of the blue on page 72, comes the first killer blow: the claim that attitudes change after behaviour, not before.

This is based on work by psychologist Daniel Kahneman, whose writing sounds fascinating and whose book Judgement and uncertainty: heuristics and biases has shot straight to the upper echelons of my wishlist.

I take issue slightly with the way Earls treated Kahneman's work, although I must stress that I haven't read the original material. Earls seems to sensationalise everything - using Kahneman's "lazy minds" theory to suggest that nobody ever makes decisions for themselves and we're kidding ourselves if we think we do. It's easy enough to understand the point he's making - and it's an important one - but does he need to exaggerate so much? It's a rather tabloid style that turned me off the book somewhat; indeed, my enjoyment of of the book fluctuated as I went through - looking something like this:

|

| How good is Herd? It varies as you go through. (Pictorial representation only!) |

The attitudes change... statement might be controversial, but, as Earls points out, it challenges the awareness-interest-desire-action model of marketing. Decisions might not be made in the frames of reference we assume.

The question is: how can we work out in what ways, and at what times, that decisions are made? The most obvious example of mass behaviour not working out as expected that I can think of in recent months was Cleggmania in the run-up to the general election in May this year. Before the election, I attended a social media summit where respected political commentator (and influential blogger) Paul Waugh proffered the opinion that the result of the election would depend less on social media than on television, as the televised leaders' debates would change more attitudes than anything else.

The first debate took place and Lib Dem leader Nick Clegg was almost universally acknowledged by those who watched the show live to have "won" it. Sure enough, the various opinion polls, with their varied fieldwork dates (some with rolling fieldwork dates; there was much excitement on the UK Polling Report discussing methodologies!) displayed dramatic increases in support levels for the Lib Dems.

But let's consider. Say 10 million people watched the debate on TV and another 5 million saw clips on YouTube or on the news, a total of 15 million who had seen the debate in some form, and not all of those would be eligible to vote. How many genuine floating voters among that lot? Surely not that many. Yet the changes in the opinion polls were dramatic. The Liberals gained up to 10% of the vote in the space of a couple of days in some polls. What was even more interesting was the fact that the bounce wasn't just an immediate thing: the Lib Dem share of support increased as time went on - and stayed high throughout the remaining weeks.

Surely this was a classic example of herd behaviour going on? Had the Twitter campaigns (for example #iagreewithnick) succeeded? Critically, were there people changing their preference who had not actually seen the debate at all, but were reacting to the hype and opinions of others around them? It's often said that voters like to choose a winner so that they can feel like they have contributed something personally to that success; this is why such positive language is used in electioneering. The Lib Dems, masters of the campaign trail thanks to the genius of Chris Rennard, have monopolised the phrase "Winning Here" as a result.

And yet come election day, the herd phenomenon seemed to vanish completely. Pre-debate polls were actually more acurate than post-debate. This seems to have been a dramatic example of the herd effect/word of mouth affecting opinions, yet when it came to the decision-making that really counted, the voters lost their nerve, or else there are other heuristics involved inside the ballot box. My feeling is that Earls' Herd theory needs re-evaluating after this, but also the research industry as a whole: the post-debate polls were largely worthless in predicting the election result, given that they gave a Lib Dem share of up to 30% right up until polling day, which dissolved completely. That's not to say there was necessarily any flaws with the methodologies used at the time... just that people's intentions can be different from their actions (as Earls would agree - it's a fundamental point of his book).

What can researchers learn from this? That intentions and behaviour are very different - that surveys can be a very inaccurate way of predicting future behaviour (what's the disclaimer that you get on investment ads?) - that perhaps word of mouth has its limits. Were the polls useless? Not entirely; they may be able to give a clue to the heuristics involved in making a decision on who to vote for. Besides things like fear, optimism, wanting to contribute to a success story...what could they be? I have no idea, but anyone who works them out accurately could be a person in great demand. I'd love to know what Mark Earls' thoughts are on the mechanisms at work in the weeks preceding the election.

Earls' argument, taken more generally, is that people are not really in control of their own lives and opinions. The key point for research is that what we think we believe in, or what we aspire to believe, or what we believe we do, and the actions we actually take, may not tally up at all. Now researchers have known for ages about the dangers of respondents giving "socially acceptable" answers to questionnaires. earls takes things further by arguing that traditional focus groups can never provide a natural environment in which we operate and interact, and that we need more organic ways of monitoring behaviour - ideally at the point at which those heuristics kick in. Does this simply point to social media research? I'm not so sure. Monitoring naturally occurring conversations - in forums and on Facebook, for example - can give a wealth of opinion data; but as with a focus group, one is reliant on opinions being put forward, however naturally that may be. Perhaps some of the newer, more sophisticated techniques might be the way forward in analysing decision-making processes - are they just hot air though?

Rich use of case studies is one of the best things about Herd. The Milgram Experiment is one terrifying example of just how irrational human behaviour can become when we feel that there is an "accepted" way of thinking. I'd never heard of it before and barely dared to breathe as I read Earls' two page account. I distinctly remember staring at the wall and saying "shit" repeatedly after reading about it. There are other, similarly dramatic (if less horrifying) examples which most "marketing" books won't come within a hundred miles of. For example, how much idle fun can you have with this Mexican Wave generator? (There are other similar modelling simulations here).

Having set the scene, Mark Earls proceeds to lay down his Seven Principles of Herd Marketing. Don't get too excited: this isn't a step-by-step bible on how to double your turnover in a year. Rather, they're a set of rather nebulous ideas, some of which are frustratingly obvious. Instead, you should continue to focus your attention on the game-changing case studies and analogies with which his arguments are made.

It starts unpromisingly. Urinals? C'mon Mark, it doesn't need a laborious analysis of the rules - that's known to anyone who's ever had a few drunken conversations (if you haven't, there's plenty of stuff on the internet). My attention wavered. Following this, however, we get into the real meat of the first chapter (simply entitled Interaction): it's lengthy, but rich in case data and ideas, and convincingly presented. We learn about markets; whether it's betting markets or financial markets, much of their behaviour and volatility is a result not of external factors, but purely the interactions between people concerned. Betting markets are similar - particularly when you start to think about either starting-price betting, or the new betting exchanges such as Betfair, where you take on the market directly. There are comparisons to be made with game theory - another subject which Earls touches on, and Thomas Schelling concedes that his entire book is really about game theory. I was chatting to a hedge fund trading mate of mine the other week, who is keen to learn more about game theory in order to improve his work; if I remember to dig it out of a locker in Holborn, I'll lend it to him - I might point him in the direction of Herd at the same time.

A fascinating discussion on metastability ensues, and how phase transitions can be compared to other social situations (for example crime levels). The pedigree of the theories is impressive: Earls rehashing Phillip Ball rehashing Campbell & Ormerod influenced by Schelling. It's no less entertaining for all that. Thrillingly, there appear to be quite a few comparisons to be made between physical systems and human ones.

I wonder if Earls has ever come across percolation theory, an area of statistical mechanics which has some striking similarities to some of Earls' material. It deals with lattices connected by nodes and the probability of some form of path finding its way through the lattice to an infinite degree. In other words, if each individual bit of mesh in the coffee percolator has a certain probability that coffee will manage to drip through that one bit of mesh, what is the probability that some coffee will make it all the way through? Admittedly that's an oversimplification, but percolation theory, which has applications in geology and materials, as well as, for example, the propagation of forest fires. Networks vary, depending on the number of connections at each node, and the number of dimensions. But the key property is that, for an infinitely large lattice - the simplest model - across a range if individual node probabilities (how porous one "junction" is) the probability of the percolation taking place jumps from zero to one around a critical probability. So there's a critical point above which the information will always find a way through. The similarities with human networks are clear: each node or person or organisation, connected to a certain number of other nodes, has a certain chance of "getting their message across" to the next person. The spread of information greatly increases as the influence or effectiveness of transmission of information at a particular junction reaches a critical level. I wonder if the Mexican Wave model could be predicted using percolation theory? It's a fascinating subject - one I came across at university - and one that merits further reading.

Earls only makes direct reference to market research a few times in the text, but when he does, he tends to be pithy. He cites the example of when a different methodology gave a completely different answer to a descriptive research problem he was involved with on shoe-buying habits. It's easy to see where his scepticism towards traditional research methods comes from: a methodology could conform to all the usual rules on sapling, validity and so on, and still give wildly different from another methodology which was similarly robust. (Could this provide a clue to where the opinion polls went wrong? Could we try a radically different methodology next time?)

Following on from Milgram's experiment, Earls then examines the models of influence: how we are all influenced, by whom, and in what way. He thoughtfully considers various descriptions of the types of people who are "influential" (though the definition of influential remains somewhat shrouded). There is the Opinion Leader approach - where one in fifteen are "social influencers". There is the "early adopters" model. Malcolm Gladwell has his ideas. Earls doesn't conclude in favour of any one approach - or against any for that matter; personally, I think that you can't just define what an influencer looks or sounds or behaves like - it simply depends on the situation. Opinion Leader talk about MPs, CEOs and community leaders. That all seems a bit predictable to me. I'd say it's much more of a social personality thing: in my experience, those people who are natural leaders and natural influencers within social spheres are the most exuberant, most outgoing, funniest, most interesting people. They're the ones who are good at everything - from rugby to pub quizzes - and don't waste a minute of their time lying around on the sofa but are involved in loads of activities (although they always seem to be good at computer games too, ironically). The ones with god jobs and attractive partners (they're probably attractive themselves, too; good genes, I suppose). In other words, the ones you're jealous of. The ones who suggest a trip to the pub and the rest follow. The ones everyone else is jealous, and wants to be like, and wants to copy. Is it possible to pinpoint what sets these people apart? I don't know. This does, however, extend to internet forums, where again there are influencers and leaders; this does not correlate with post counts. It's something I might write a post on at a later date.

The next couple of chapters of Herd fade away very slightly, with a rather forgettable discussions on word-of-mouth marketing - although I wholeheartedly agree that buzz isn't something you can conjure up, and that half of these word of mouth, buzz and social media "conversation" agencies are charlatans. A slightly sanctimonious chapter saying "just be yourself" follows; presumably this was the chapter where Earls convinced his publisher that this was really a marketing book rather than a popular science one, as there are quite a few case studies. Again, however, while a little predictable in its ideas (make good products, be nice and smiley to everyone and everything will be OK) it's written in a gripping style. He defines a "Belief Business" as one which applies its ideals across all forms of its operations. He gives several examples; the most obvious one that can think of in my experience is The Lexi cinema. Run by volunteers, with all its profits going to charity, it's not just for the bleeding hearts - it's a lovely comfortable interior with great decor, friendly staff, a bar (yes, you can take in your pint), no ads, a personal introduction to the film by one of the friendly staff...all in all, it's easily the best cinema in London (and 10 minutes walk from me to boot). The damage is a tenner a time, but the overall experience is so far removed from the nearest alternative (the multiplex on the North Circular) that it's worth every penny. The Lexi has been cited before as a social media case study (not sure where the article is or who wrote it but suffice to say that their Facebook and Twitter pages are active, conversational, multilateral and give you plenty of reasons to follow them).

Earls is back on compelling form when talking about co-creativity - with countless examples, across platforms and industries (and outside industry!), of group collaboration proving to be more effective than one "genius". His nineteenth century engineering example was particularly strong; more up to date was his discussion of co-creativity in the software industry. Perhaps he missed the two more obvious examples of collaboration in the technological world: APIs, where programs and applications such as Twitter and Google Chrome are opened up, allowing developers to create extensions and tools to really enhance the user experience; and of course the ultimate co-creative project, Wikipedia. There are plenty of academic studies on the wiki phenomenon out there so I won't embarrass myself - but I will point you in the direction of one of the most interesting articles on Wikipedia: about its own accuracy.

Herd finishes on a slightly damp note of don't bother defeatism again (hence the slight tailing off of my enjoyment graph!) but I found myself coming away with more and more examples of

One example that always gets to me, although not strictly an exercise in herd behaviour (it's my blog and I'll cry if I want to), is choosing who to sit next to on the bus. If you go upstairs and each two-person seat has exactly one person sitting on it...how do you choose where to sit? Now don't say "random". There will be some sort of reason. Perhaps there's a simple rule you take: the front seat, or the one closest to the stairs. But let's say you don't. OK, if you've got the whole bus to choose from, then certain people rule themselves out straight away: those sporting loud headphones, gross obesity, and cans of special brew are unlikely to have their adjacent space taken away from them early on. But then who? Trying to deconstruct my own subconscious, I think I aim for someone as neutral and bland as possible, someone who is unlikely to make a fuss, someone who keeps their stuff on their side of the seat, someone who won't make a big deal of getting out. I don't think I'm fussed by male or female...although if I decide to sit next to a woman, it can't be the most attractive one there (too obvious), although I'll err on the attractive side of average if possible. It'll probably be someone of nondescript age (ie middle-aged). And although consciously I would never choose on racial grounds, having read Schelling I'd love to know statistically/historically whether my seating habits are biased towards white people. They probably are. Incidentally, as a schoolkid, I always used to get paranoid if I was the last person to be sat next to. In truth, I probably still do.

I could go on all day providing examples. Just the other day I was in Edinburgh at the festival (I've put some reviews up here). I went to see stand-up comic Stephen K Amos - one of the better and more dependable middle-of-the-road comedians in this country. At one point, a bloke got up noisily to go to the toilet; when he was gone, Amos decided to try a little experiment in herd behaviour (or peer pressure as he put it). He briefed us on what to do, and when the chap came back with a newly empty bladder, Amos casually said "now, c'mon folks, let's be honest here. How many of you used to pick your nose and eat it when you were younger?" As one, we put our hands up...and, sure enough, chappie's hand went up with the rest, whereupon he was stitched up royally by Amos, to his embarrassment (and our mirth).

Mark is a constant critic of the traditional focus group - his arguments perhaps point to weaknesses in even the latest trendy research-by-crowdsourcing and online communities (MROCs) - that they are artificially created and therefore can never be a place to watch true, natural interactions between people. But there is a difference between online communities and focus groups and that is timescales. Scientists can create artificial environments very easily - whether it's artificial reefs or contrived forests - and, although nature will take a while to adapt, in time the relationships between creatures and plants will adjust as normal. Hell, Big Brother was a great concept at first, and no matter how much the producers contrive to force increasingly incompatible and decreasingly interesting people who they think will be good for a fight/shag/ratings (delete as appropriate), even in a short space of time true human emotions, relationships and frailties poke out from under the veneer - and thanks to the camera work of Tony Gregory and his team, every glimpse, every pained expression, every faltering relationship will be captured on film (although, of course, the editing reduces it all to fighting, shagging and ratings). If left alone, a garden will start to sprout weeds and brambles and similarly, now matter how artificial an online community is at first, if left alone, the true insight can appear. Weeds and brambles encourage the real money shot back garden wildlife like bees, mice and foxes; perhaps if left to go to weed, online communities can also provide that rich interaction of the type that Mark Earls thinks is so elusive.

My mum (like my dad, also a shrink; breakfast-table conversations could be quite stressful) was talking to me the other day about a conference organised by the Tavistock Institute she attended in Leicester many years ago. Ironically, it's a conference on group behaviour; she told me that what was fascinating was the way that over the course of the week-long conference, groups, factions and schisms grew naturally - which all began with a rather heated discussion between the smokers and non-smokers at the conference. In the space of a few days, delegates had clustered together around natural leader-types, to the extent that cross-group interaction was almost non-existent.

"An indispensible manual for the Web 2.0 era" extols Matthew D'Ancona in the list of endorsements on the back cover. Would I be right in thinking that D'Ancona has missed the point of the book entirely? The "Web 2.0 era" isn't something new, and nothing has changed about the way people interact and behave. The behaviour just manifests itself more clearly. Opinions, trends, and the propagation of content and views can just be traced quantitatively much more easily.

Herd could be described as the Da Vinci Code of marketing. It relies a little too heavily on shock tactics, the writing style is an acquired taste, and it draws some conclusions that might be distinctly dodgy, but damn, it's good fun getting there: you'll gobble it up page after page, and come out on the other side feeling quite liberated, with some pretty major questions in your mind about how human beings work, and whether our communications efforts could all be in vain. One of those rare things that might actually justify the description "essential".

Saturday, 28 August 2010

Camille O'Sullivan - Chameleon - review

Nevertheless, in a show of less than an hour and a half, it was a shame to see so much duplicated material, even if it was some of the best songs from the previous time. Tom Waits's All the world is green, Brel's Amsterdam (equally extraordinary performance second time round), Nick Cave's The ship song and Dylan's Don't think twice, it's alright took up a substantial proportion of the show. It would be nice to see the band showcased a little more, as well, and Camille's range of songwriters is limited (all the more irritating given that she asked for repertoire suggestions on her Facebook page a few months back, then slipped into her usual Waits-Cave-Brel-Bowie hitlist).

But to show some irritation at seeing a show without many changes is churlish, as the fact of the matter is that Camille is simply a massive star. She has it all: performing ability, charisma, presence...and a stupendous voice. It was a special moment for me to hear her take on the music of Leonard Cohen, as the two singers are two of the greatest live performances I've ever seen; Tom Waits's God's away on businesswas another highlight. It's a shame that she has outgrown more suitable venues, but sitting in the sixth row, the sparks were exploding in all directions.

Verdict: Not the same seeing her second time round, but damn! this girl can perform.

Markus Makavellian's International Order - review

Markus Makavellian's International Order (Drew Taylor/Proud Exposure, Underbelly)

Verdict: tight writing and a flamboyant performance make this a captivating hour after a wobbly start.

Impressionist Gardens: asphyxiating colours

The first room, Towards the Impressionist Garden, explores some of the work pointing towards the techniques and styles that the Impressionists proper would use, and an increasing obsession with the natural world. The vibrancy and sensuality of Eugene Delacroix's Still life with flowers (1834) - a rust-coloured background highlighting the heady flowers. I also loved Corot's Parc des Lions at Port Marly (1872) with its silver birches dividing a brother and sister.

| Mary Cassatt - Summertime (1894) |

|

| Leon Frederic - The fragrant air |

|

| Gaston La Touche - Phlox |

What surprised me was that although there are only a handful of works by the blockbuster names (Monet, Renoir, Manet, etc), the exhibition does not suffer one bit and there is absolutely no feeling of there being and "filler" (which was the problem with the Impressionism & Scotland exhibition at the same gallery a couple of years ago when they padded out the good stuff with a load of Scottish stuff from their own collection). Indeed some Scottish works were amongst the highlights: Arthur Melville's A cabbage garden (1877), placed later within the utilitarian and market gardens section, was one, with its gardener knee-deep in blue-grey cabbages. Belgian James Ensor's The garden of the Rousseau family (1885) also sits in this section, a real magical feeling, not to mention the spooky cabbages looking like eyes.

|

| Monet - The garden at Vetheuil (1881) |

Other highlights included a Gauguin (Skaters in Frederiksberg Gardens, 1884) where the red autumn leaves highlight the coldness of the ice; Monet's pair of paintings of The parc Monceau in Paris, where he deliberately avoids the brilliant parts to concentrate instead on a shadowy corner; and The rainbow (1896) by Leopold Graf von Kalkreuth, who captures the feeble white sunlight contrasting the dark clouds perfectly. Serene figures shiver as they contemplate the rainbow.

|

| Pissarro - The Cote des boeufs at L'Hermitage, 1877 |

|

| Joaquin Sorolla y Baptista - The garden of Sorolla's house (1920) |

The final rooms, featuring later Impressionist works, are the most dreamlike and fantastical of all. Nature gets sinister with Van Gogh's Undergrowth while a couple of Monet's most misty, dimensionless waterlily works are also exhibited. Henri Le Sidaner - another I'd never heard of - made a wonderful piece called An autumn evening in 1895: an air of soft beige mystery surrounding a woman walking alone at gloomglow in profile. Meanwhile, Joaquin Sorolla y Bastida's The garden of Sorolla's house (1920) is idyllic, with luminist shimmering perfection in a garden framing a dazzling white chair. It's an extraordinary work. Another Van Gogh work, the rather stark, raw Garden with path (1888) feels almost harsh and uncouth by comparison to the earlier lushness (presumably what contemporary critics felt as well!).

The very best is left until last, however, with works of rose gardens on the final wall - four heady, indolent washes of colour and texture: Klimt's Rosebushes under trees is one highlight but my favourite of all is the very final work - another one by Le Sidaner: The rose pavilion, Gerberoy (1938) is a wonderfully evocative work of colour and beauty.

Wednesday, 25 August 2010

Julien Cottereau - Imagine-toi: more than just bubblegum

Verdict: gentle and uplifting, worth and hour of anyone's time.

Thrilling Brandenburgs from Gardiner topped by stupendous brass

To my knowledge, I've never seen a Gardiner concert performance before - and it was worth waiting for: the Brandenburg Concertos are, for my money, about as close to musical perfection as you can get. I've known them back-to-front since I was about two feet high thanks to sitting on my dad's knee listening to Menuhin and Pinnock recordings (with the odd Wigmore trip thrown in). You'd never have anything at the Wigmore resembling the chaos of getting the audience into the auditorium in the first place at the Cadogan Hall though: they hadn't manage to get the audience completely in by the time the concert started. I promoted a concert there about four years ago and it was similarly shambolic; they no longer have the excuse of being a new venue.

We kicked thing off with the Concerto No 1, never one of my favourites, and it was a thrilling ride. Gardiner launched into the opening movement at a breakneck pace and the exhilaration never let up. It was a quite extraordinary performance. Swooping changes in colour and dynamics, a perfectly balanced second movement, and crisp main themes were excellent. Dominating everything were the horns. They hurled themselves into the fray, thrashing out cross rhythms like their lives depended on it. The music around may have been refined; the horns bullied and harried, "hooligans breaking up the party" as Gardiner observed during his excellent, and lengthy, discussions with Catherine Bott during the shifting of chairs between pieces. But these weren't modern French horns, but old-school hunting horns - nigh-on impossible to play. Both players demonstrated incredible technical skill - particularly Anneke Scott, whose trills and virtuosity were out of this world.

The slow movement was perfectly balanced, but it was in the beautiful polonaise, buried deep within the menuets (and shortly before the ludicrous horn & oboe trio), which provided one of the moments of the entire concert: following the lulling of the strings with their appoggiatura-like duplets, halfway through, where it breaks into a dance (you know the bit): suddenly, the strings crackled into electric staccato. My jaw nearly hit the floor - it was another thrilling moment. As Wagner once said of Beethoven's seventh symphony, it was the apotheosis of the dance. As a whole, the first concerto was a spectacular success.

The sixth was up next. Never a blockbuster, I've always had a soft spot for it thanks to its unique colours - dark yellows, mauves and browns provided by the instrumentation. With no natural high voices, the violas, gambas and cellos provide a rather oblique feel. The key (B flat) heightens the effect. The first movement, which has no real tune but is just a wash of dark tonal colour in languid, almost turgid rhythms, is almost impressionistic and I can think of no other piece like it. The group, now conductorless, played the colours up marvellously. The final movement, once again, as with so many of the Brandenburgs (as Gardiner emphasised) provided the EBS to show off their dance music making skills.

All the Brandenburgs are special to me but the fourth is especially close to my heart and was a disappointment. Kati Debretzeni was very accomplished in the virtuoso violin role, but I found Rachel Beckett and Catherine Latham - especially Beckett - extremely dull. The first movement plodded along, with one-dimensional staccato-by-numbers recorder playing, with little variation in tone or style. After the joys of what we had heard so far, I felt let down. The slow movement was similarly uninspiring, with only some excellent orchestral balance making up for dull solo playing. Only in the presto finale did the piece really spring to life - sparkling virtuosity from Debretzeni in the background supporting bubbly recorder solo lines. A wonderful ritornello came out of nowhere shortly before the end, reminding us that however brilliant the soloists might be, Gardiner remains the star of the show.

Technically, the day was split into two separate concerts, so after finding a paella stall just off Sloane Square (the only place that served something more promising than rocket ciabattas) it was time to go back for the second part. Among a set of some of the best music ever written, the third shades it as my favourite of all with its perfectly balanced nine solo strings and incredible fugal lines. This, too, was a riveting performance. We heard a lengthy violin improvisation as the non-existent slow movement (perhaps a bit of a partita); various conductors have done "all kinds of wanky things" according to Gardiner (Catherine Bott did well to keep her composure at this point, with producers doubtless falling off their chairs).

As wonderful as the melodies are throughout the Brandenburgs, the best thing of all is the harmonies and most of all the driving pedal basslines. None more so than in the third, where the tension is ratcheted up to fracture point at times with the bass. Although a soloist in the third, special mention must be made of the principal cellist (I will have to wait until I get back to London to check my programme for his name) whose continuo playing I thought was superb.

Gardiner and Bott indulged in some cringeworthy flogging of dead horses in repeatedly describing the music as "funky". They're really "boogying down", we were told. Set toes to curl and ears to shut. That said, I could see an obvious comparison: in the late 70s and early 80s, heavy metal guitar solos became ever more lengthy, virtuosic and gratuitous - and self-indulgently brilliant; I can't think of a better way to describe the harpsichord solo in the fifth. Ever since I was a kid I've loved the way the rest of the band gets out of the way to admire the harpsichord and this was no exception. The slow movement of the fifth always strikes me as the only movement in the entire catalogue that is genuinely dull - although the dainty last movement makes up for it.

We finished on a high note with some facemelting natural trumpet playing from Neil Brough in the second concerto, with oboe, violin and recorder providing able support. Brough didn't put a note wrong throughout and the final movement's lightning pace was a fitting way to finish.

Monday, 23 August 2010

Reviews: Daniel Kitson "It's Always Right Now Until It's Later" a winner but Grandage directs limp "Danton's Death"

Danton's Death (National Theatre) **

Daniel Kitson is the master of coaxing the most out of something so tiny that after an hour and a half in his company, you feel you'll be able to spot something idiosyncratic or beautiful in the tiniest thing you pass. It's Always Right Now... is typical Kitson fare these days, to be honest, and if you've seen any of his more recent material this will have a familiar ring to it. But that doesn't detract from it in the slightest. The night I went was the final preview night at the Battersea Arts Centre, before he transferred to the Traverse in Edinburgh for a (more expensive!) run which is currently in progress. He warned that it might be slightly shambolic, which is was at times, but not in a bad way. Kitson remains incredibly nervous, and was easily put off by shuffles in the audience; eventually this developed into a full-blown heckle from some bell-end sat next to me. As I pointed out to him afterwards, Daniel Kitson hasn't done stand-up since about 2004 (his complaint) but (as the knobwhiff found out) he is possibly the greatest exponent of putting down heckles in the world. The turbomong was duly despatched with, with savage efficacy.

Back to the show. Kitson tells the tale of two lives, independent of one another, in fleeting moments: falling off a bike, or a moment on a bus. It's loose and sprawling, but the tenderness with which he spins his yarns, and acute social observations, make it an utterly compelling 90 minutes. I emerged wide-eyed and inspired to look for more beauty in the mundane: if Kitson has a message, it is that all our lives are extraordinary. Which is an inspiring thought in itself.

Donmar Warehouse director Michael Grandage has been exalted to near-legendary status in recent years with some brilliant productions: I can vouch that his Othello with Chiwetel Ejiofor and Ewan MacGregor, Hamlet with Jude Law, Ivanov with Kenneth Branagh and Twelfth Night with Derek Jacobi were all superb.

With Danton's Death, however, Grandage hits a massive dud. It is a lengthy French Revolution saga which is completely one-dimensional (lots of shouting) and linear (brave revolutionaries jockey for position and make "inspiring" speeches, ad infinitum). Toby Stephens as Danton is completely indistinguishable from the rest of the cast, and the only memorable feature, a nice guillotining gimmick at the end, only goes a small way to recouping the time wasted in seeing this show. Avoid.

Sunday, 8 August 2010

Lush, but it ain't Tchaikovsky, Valery

An hour's queueing was enough to secure a gallery place to watch the world's greatest all-star orchestra on Thursday night. It felt like seeing the Harlem Globetrotters - the fact that it was Gergiev and Mahler made the gig that little bit extra tantalising. The result: a wonderful performance...but memorable Mahler it was not.

The Fourth Symphony isn't one of the blockbusters, indeed it's not one I'm particularly familiar with. The opening was arresting, with an exaggerated tempo change to the string line. Decidedly microtonal intonation marred the second movement - there seemed to be some problem with one of the horns. The third movement passed without incident; the end of the movement is bizarre, with a clashing gears tempo change and unexpected modulation late on. Camilla Tilling's soprano was beautiful throughout the finale, although solo vocals don't carry well up to the rarefied atmosphere in the gallery.

Throughout, the tones produced by the musicians were out of this world. The combined orchestral colours sounded like the Albert Hall organ at times, such was the richness of the sonorities. Strings were superb throughout. Aristocratic horns and clotted cream heavy brass (I particularly liked the tuba), but things were too measured, especially in the Fifth. The oboes didn't yowl, the clarinets weren't petulant enough. The first movement of the Fifth was taken at a majestically sombre pace, the triplets given paramount importance. I liked the interpretation. The second movement had some wonderful moments, notably the exposed cello line which was spinetingling (even hearing it puts an amateur cellist into jitters, it's a horribly stressful passage to play!). The gigantic Ländler, a wild, rough jamboree, had too many ballet shoes and not enough clogs. As the movement progresses, it flirts with bitonality, and can feel like a party that's gone out of control as the harmonies and crossrhythms descent into anarchy. There was none of that here. The Adagietto was perfectly balanced, and The Greatest Note In All Music welcoming in the final movement was as pure as can be. Only then, in the final movement, did the orchestra sound truly Mahlerian. There was a swagger in the woodwind and aggression in the brass that had been lacking somewhat.

Had we been hearing Tchaikovsky, this would have been a stupendous performance. As it was, the evening was a masterclass in tight, marshalled orchestral playing. But a little more Mahlerian entropy would not have gone amiss.

Thursday, 15 July 2010

One-on-One Festival (part deux): Ontroerend Goed leave the best until last

What a week this has been. The emotional rollercoaster of seeing the One-On-One Festival on Sunday (read that review before this one if you haven't already), the horror of Carmen Funebre, then last night a trip back to BAC to further the experiences of the other day. With it, I was hoping for some sort of closure. Closure I got.